Art is an immediate mood booster, and changing the art in my practice is an uplifting and inspiring process. I do not buy art to hang in my practice. Instead, I hire artworks from Artbank, a unique Government rental program which provides direct support to Australian artists.

This blog introduces the new artworks now on display and the artists behind them. I explain what I like about the new paintings and sculptures and why they appeal to me.

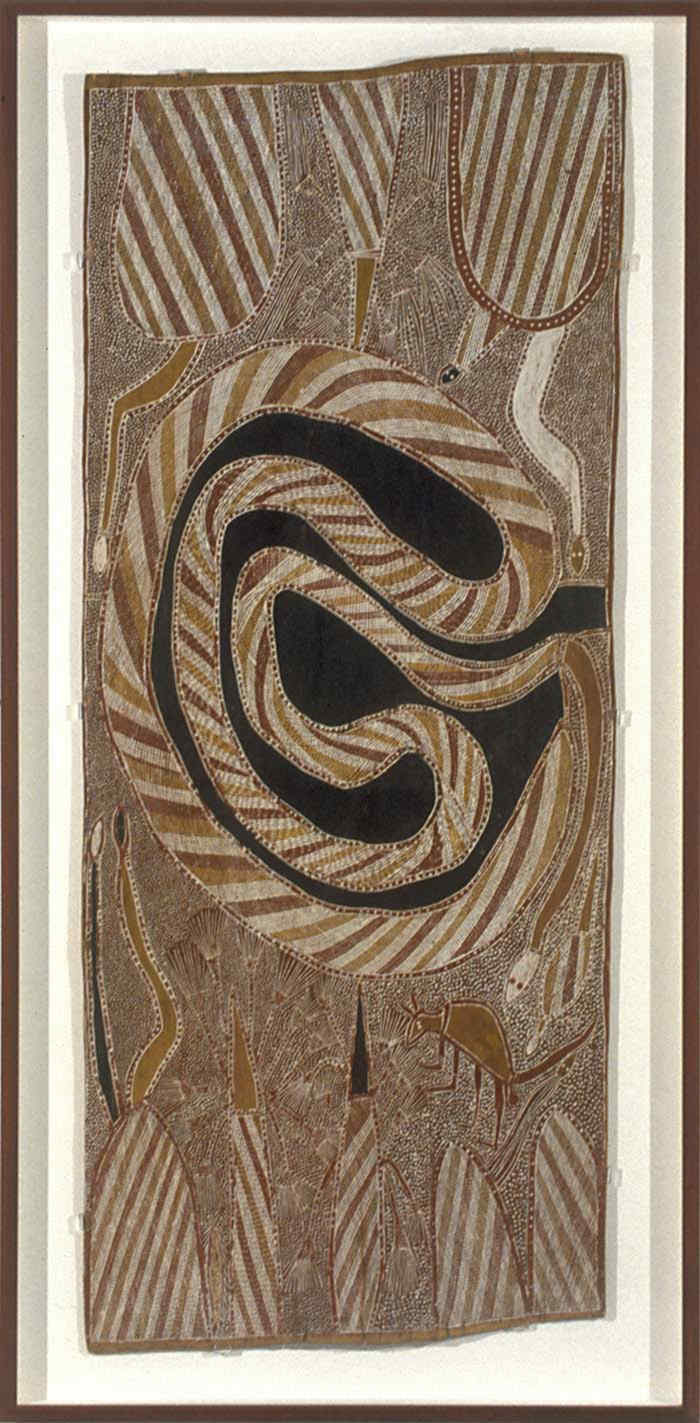

Dreamtime Legend

Julunggal, the Rainbow Snake, c.1981

Natural earth pigments on bark

The hero artwork of this new collection is a magnificent bark painting of Julunggal, (Wititji), the Rainbow Snake. Binyinyuwuy Djarrankuykuy (c.1928 – 1982) was a leading artist from Milingimbi, also known as Yurrawi, the largest of the Crocodile Islands off the coast of Arnhem Land.

This painting is magnificent. I love the rich colours and the intricate rarrk crosshatching strokes but it is the composition of the coiled, curving rainbow serpent I find most arresting. Artbank has a fantastic collection of bark paintings and I was lucky to see many of them exhibited side by side. My eye kept returning to this painting because of the coiled serpent highlighted by the contrasting black shadow. I may lack the knowledge to interpret all the symbols and meaning in this painting but I can still appreciate its power.

I also enjoy the link between this painting and Arnhem Land. I travelled to Darwin in 2013 in my capacity as National Board Chair for the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons (RACS) Board of Otolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery. I was completing a hospital inspection visit as part of the surgical training accreditation process. After completing the inspection, I visited Arnhem Land with my family. Our trip included a visit to Injalak Arts, an Aboriginal owned organisation, where we observed artists at work.

Bizarrely, bark painting also reminds me of Charlottesville, Virginia, where I did my post fellowship training at the University of Virginia. The Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection, in Charlottesville, is one of the finest collections of Aboriginal art outside Australia. Television mogul and entrepreneur John W Kluge amassed an extraordinary collection of Aboriginal art after he first attended the exhibition, Dreamings: The Art of Aboriginal Australia, at the Asia Society Galleries, New York City in 1988. His many visits to Australia over subsequent years resulted in the purchase of more than 600 artworks. I have mixed feelings about these works leaving Australia, but I am inspired by Kluge’s ability to appreciate the beauty and splendour of Aboriginal art.

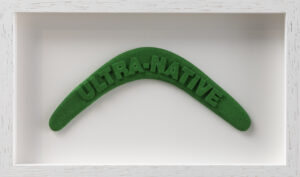

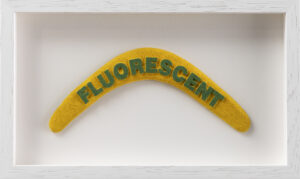

Words as hunting tools

These colourful boomerangs, at first glance, are bright and fun. I urge you to look closer. This series of sculptures is by Keemon Williams, a queer Meanjin (Brisbane) based artist of Koa, Kuku Yalanji and Meriam Mir descent. Keemon explores words as hunting tools. If you want to learn more, and hear Williams in his own words, I encourage you to listen or read ABC Arts Works story about Wurrdha Murra, the NGV’s permanent First Peoples’ gallery space.

Many thoughts and emotions come to mind as I read Williams’ words. There is a tension behind the cheekiness which demands and commands respect.

Old friend, different story

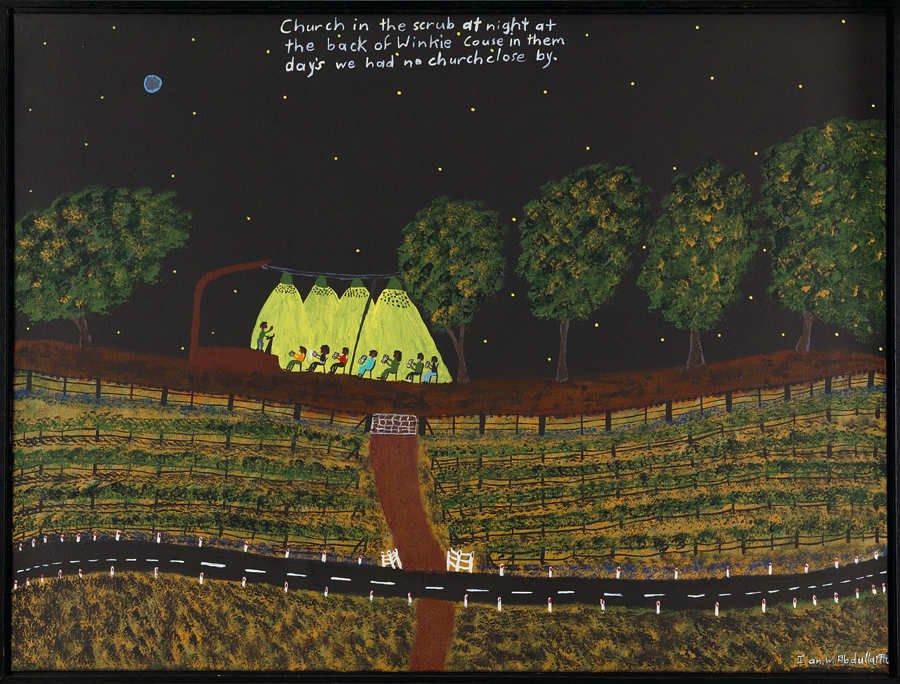

I am delighted to have another Ian Abdulla painting in my practice. Abdulla was a Ngarrindjeri artist living the Riverland region of South Australia whose work explores his experience of poverty, dispossession, and community growing up in the 50s and 60s along the Murray River.

Church in the scrub at night, 1994 hangs above my desk. Back in 2016, when my practice was in St Vincent’s Clinic, our Artbank collection included Ian Abdulla’s Mother with fish, 1960. The painting hung in my consulting room and continued to haunt me, in a good way, long after it left. I know it was also popular with my patients.

Church in the scrub at night, 1994

Synthetic polymer paint on canvas

Abdulla’s paintings are incredibly vivid. His use of text, combined with the simplicity of his words, makes me feel as though he has snuck into the room and is personally describing the scene.

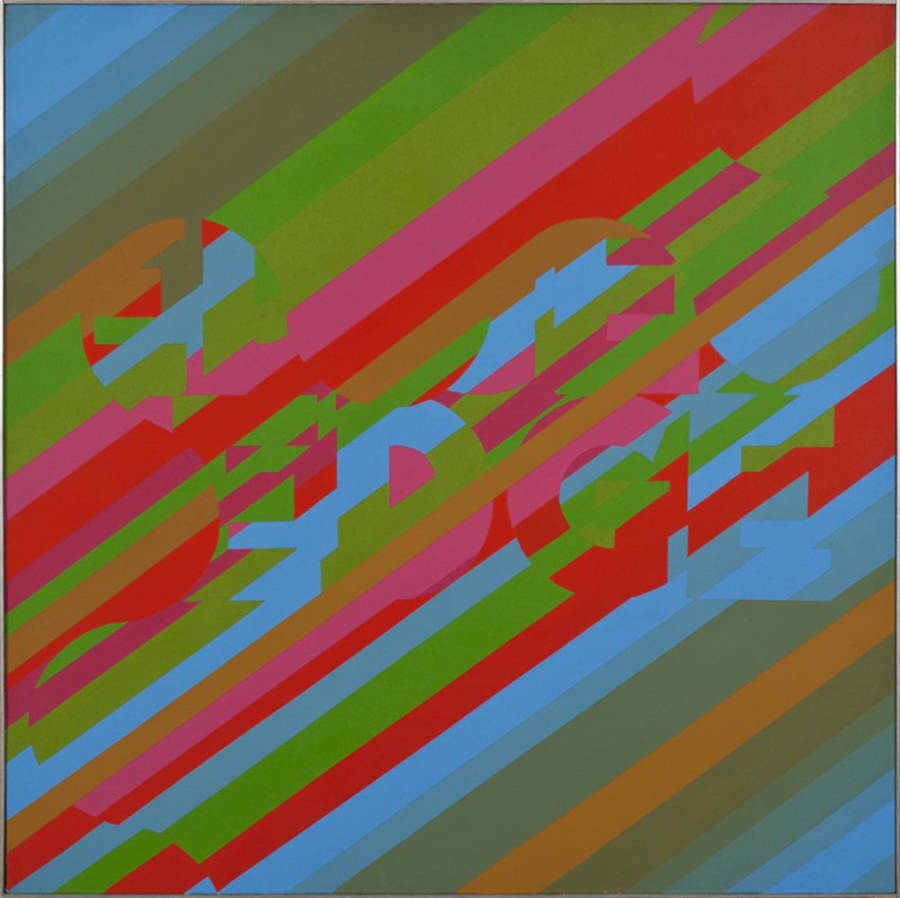

Among Others

The other new paintings include works by Col Jordan, Gemma Smith and Jamie Boys. All of them make me look and make me think. Three of these last five paintings are abstract, providing an optical contrast to the other works. Col Jordan’s Hard Edge hangs in my office. Hard-edge painting, also referred to as Hard-edged, is a style of painting in which abrupt transitions are found between colour areas. It recalls the work of artists such as Wassily Kandinsky. The first art-print I bought and framed, back when I was a medical student, was one of Kandinsky’s, but I only made the connection as I sat and wrote this blog.

Hard Edge, 1974

Synthetic polymer paint on canvas

The two paintings by Gemma Smith date from 2006, placing them towards the beginning of her impressive and continuing career. It is intriguing to look at these paintings in conjunction with photographs from their gallery installation. If you scroll through the photos from 2007 you will see the Adaptables sculptures Smith created in conjunction with the paintings, some of which are now part of the Museum of Contemporary Arts’ permanent collection.

Gemma Smith

Untitled 14, 2006

Painting – Acrylic on canvas

Gemma Smith

Untitled 10, 2006

Painting – Acrylic on canvas

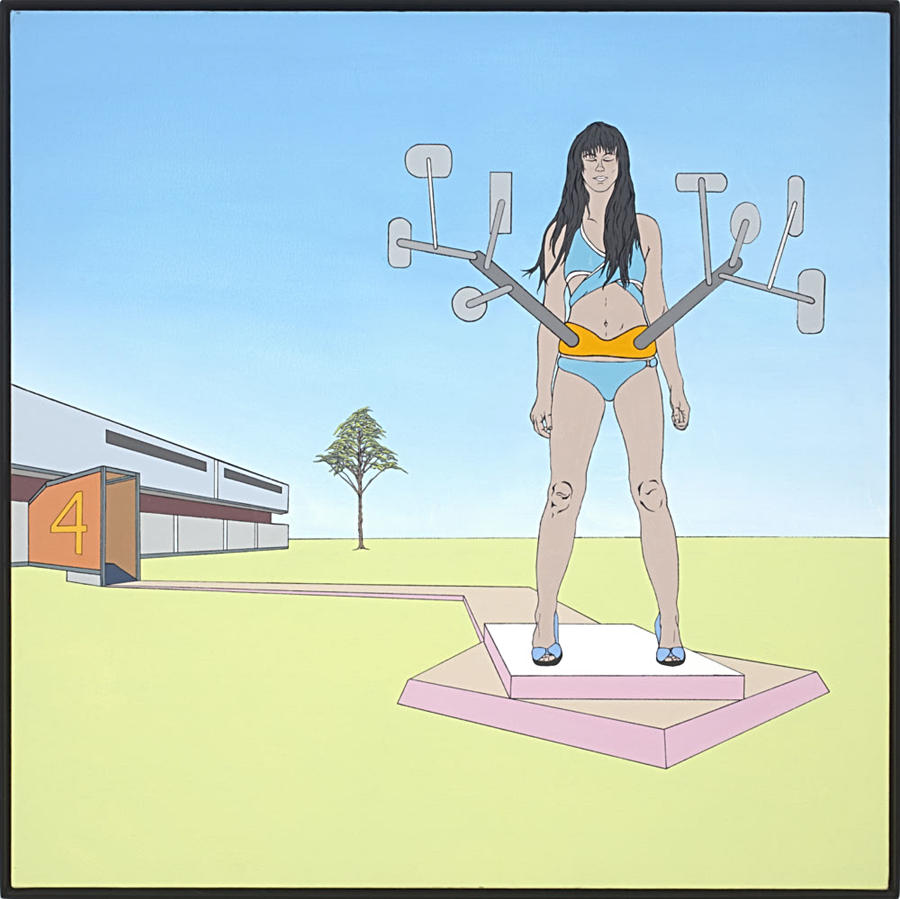

Jamie Boys’ paintings are bold, bright and kooky. They should tell you something about my sense of humour. There are a pair of his paintings in the practice and their titles do a great job of explaining the ideas behind them.

I initially thought the “monkeys” were referring to the phrase, “to have a monkey on your back.” Writing this blog has made me look more closely at the title of the painting. Now I can see Boys is directing us to a different idiom, “one monkey does not stop the show”. In other words, one setback should not impede progress. An encouraging reminder for surgeon and patient alike.

One monkey don’t stop the show. What about …, 2008

Synthetic polymer paint and ink on canvas

If you can’t see my mirrors, I can’t see you, 2007

Synthetic polymer paint and ink on canvas